Communicating Science

When we talk about science with children, are we really communicating in a way that children understand?

By understand, I mean:

-

Do they understand the language?

-

Are they understanding the concept?

-

Are they fully engaged?

In this article I will discuss some of the many different ways that adults talk about science with children and give some ideas for how we could do it better.

What happens to your lunch?

The obvious question when talking about science is, should you use challenging scientific words? The issue is that students can easily struggle with or misunderstand information if they don’t understand the terms used.

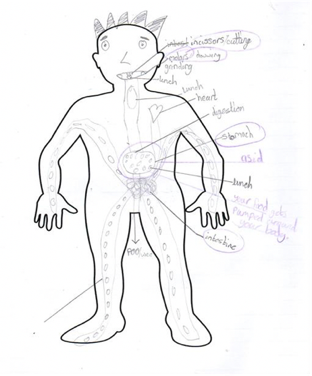

I realised how easily children can misinterpret information when I asked my Year 4/5 class to draw on a body map what they thought happened to their lunch. One boy (age 10), who was always keen to please, drew tubes going down the arms and legs. He then drew lots of tiny circles inside the tubes.

“Tell me about these,” I asked him.

“They are bits of my sandwich,” he replied.

He went on to explain that all of the body needs the food, so after we have chewed it, small lumps of sandwich travel round the body in the blood to give his body energy. He was quite sure about this because a previous teacher had told him that ‘the blood carries nutrients all around the body.”

He had some understanding of the purpose and process of digestion and he hadn’t been told anything that was incorrect. He simply interpreted ‘nutrients’ to mean his sandwich.

This particular little boy spoke English as an additional language (EAL) which made me wonder how many words that we use confidently as adults, do we forget to define or explain for children.

The language of science

The language of science can be very different to familiar everyday English. Most adults know that ‘nutrients’ are the basic food types that we eat. They could tell you that carbohydrates, proteins, fats, fruit and vegetables, vitamins and minerals are nutrients. These are all listed on the backs of food packets.

We cannot assume that children know this; the basic units of a packed lunch from a child’s perspective could be pieces of sandwich, a crisp, a piece of banana, a cereal bar.

We must explain science vocabulary carefully to avoid children developing and retaining misconceptions.

Children need to understand and practice using new vocabulary, just like they do when learning a foreign language. An obvious way to do this is through conversation. As a teacher of parent, you can ask children to talk about their work. In a classroom this could be individually or in small groups.

Posters and presentations

Posters, pictures and annotated diagrams can give children the chance to use new language orally and visually.

This strategy can be particularly helpful for children who struggle with writing. Discussions will enable these children to demonstrate that they do have science knowledge and skills. In contrast, a written piece of work might mean that these children cannot show these science-based skills. It is crucial that teachers realise when poor literacy skills are affecting a child’s attainment in science.

A child (age 9) made a poster to explain that gravity was a force responsible for pulling objects towards Earth. They were able to use appropriate science vocabulary to explain what was happening in the picture.

Many children enjoy making a presentation in front of their peers, older children often enjoy showing PowerPoint presentations they have created on computers. Bear in mind however that not all will. For some children an oral presentation is a daunting experience and we need to be aware of this too.

The drama of public speaking

Thinking about the quiet shy children in my class, I began to wonder what strategies other than oral presentations I could use to provide children with opportunities to talk about science.

When my year 4/5 children were struggling to understand the differences between the processes of fertilisation and pollination, I asked the children to act out what was happening. Suddenly all the children were engaged, even the quiet ones who rarely put their hands up. The children gave each other instructions using scientific vocabulary throughout, correcting each other as appropriate.

As well as being a stimulating experience for the children, it was a valuable assessment tool for me as I could identify which children had misconceptions and support them. On another occasion, I used drama to act out the journey of a red blood cell around the body with Year 6 children. Again, I was surprised and impressed by the degree of peer support given to the least confident children.

The joys of being an onion.

There’s a hilarious series of Calvin and Hobbes Cartoons (by Bill Watterson) where Calvin is overjoyed at being cast in a school play as an Onion. The play is called “Nutrition and the four food groups”, a clear cross curricular activity!

Mixing drama and science might be regarded as an odd combination but the division of arts and sciences is a very modern construct and one which is not seen by young children. It is normal for children to act out their experiences through play, and is encouraged in the Early Years, so why not in primary school lessons?

Each time that I have tried using drama to support children’s learning, the children have received it enthusiastically. In contrast, I notice that many teachers have a fear of drama, probably because they associate drama with the expectation of a performance. This is not the case when the drama is a tool for learning within the classroom. Drama means demonstrating knowledge and understanding, and helps children to communicate, which is, after all, what is important in science.

Why to go off script

There doesn’t have to be a script. Instead, the children can create the dialogue in real time which develops their critical thinking skills. They learn as a group, seeing several possibilities and responses to a situation unfold at the same time. This introduces the children to comparison; seeing lots of ideas and making a judgement as to which is the more appropriate.

It seems to me that this mirrors the skills of a scientist; collecting and reviewing data before making judgements, so again experiencing drama will help children to develop their ‘scientific thinking’ skills.

An added benefit of drama in any lesson is that it can be recorded by camera or on tablets, and played back to the children. Watching themselves, or their peers, provides another opportunity for children to talk and to reflect on the learning. If children begin to reflect, they must become more effective learners in all areas of the curriculum.

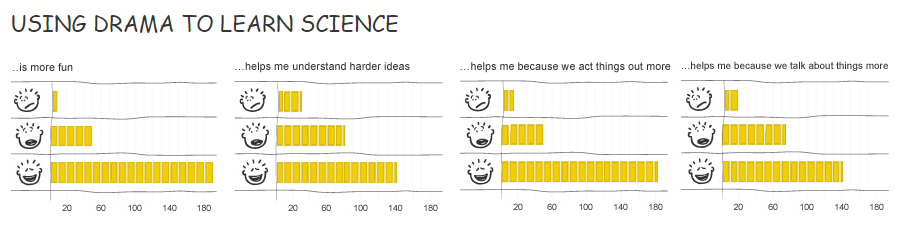

What is the impact of using drama with science on children?

My own observations when using drama are that the impact on children is greater enjoyment; children really do value ‘doing’ over ‘writing’. I think that drama provides a more inclusive experience for more of the children, compared to a lesson that is book based. Other teachers describe science as being more ‘real’ to the children, and children remember the content for longer. See this CPD unit for more details.

Arguing your point

A slightly different approach to get children actively involved and talking is to introduce arguments.

As a research scientist myself (before teaching I was a biochemist), I know that one skill needed by a scientist is the ability to argue for one opinion over another. Children seem to have an innate ability to argue- what child doesn’t like to challenge an idea from time to time? There is a fabulous CPD unit exploring argument as a teaching and learning strategy for primary science available free here. This unit is aimed more towards older primary school children. It explains how a teacher (or any adult – could be a parent at home) can facilitate effective discussions. For example, sometimes presenting an opposite point of view to help children to organise their ideas.

One child’s comment really made me think about how I make my lessons accessible to all the learners in my class. They said: “When you only write or just do something you can go along with everyone else and no one realises you don’t understand.”

A teachers says, “My lower attaining children feel more included when they work with mixed ability. They are more likely to contribute.”

It is hugely important that all children can participate in science lessons and learn about science. Comments like the ones above suggest that whilst it is very important that all children learn to read and write effectively, these methods do not equate fully with successful learning. This is especially poignant for those with EAL, SEND, or dyslexic issues.

Communicating through technology

When I was thinking about other ways to stimulate children’s science talk, it also occurred to me that modern technology offers us many different methods for communication. As children are growing up in an ever more complex technological world, surely it would be appropriate to use some of these methods to enhance learning. If we want children to talk about science, then why not talk to a scientist?

Obviously a real life visitor would be great but there is technology enabling far easier options.

A wonderful website which allows children to ask questions is ‘Ask Dr Universe’. The website is aimed at children (though anyone can ask a question) and provides answers to questions in all areas of science. Children can post their own questions online or search previously asked questions and find answers from scientists based at Washington State University.

Another option is a video call where a scientist can literally be transported to your classroom mid expedition. A leader in this field is EncounterEdu who enable students to talk to scientists from regions such as Svalbard or the Indian Ocean. We’ve blogged about their last few live events and there are more coming up this autumn.

We’ve also found FaceTime a Farmer and Skype a Scientist but have not yet spoken to anyone who has given these a go. We’d love to hear whether you would recommend the experience. (https://wowscience.co.uk/contact/)

As well as talking to scientists, you could go on a your own virtual school trip using google expeditions.

Enriching not replacing

In summary, I think we need to remember that science is a new language to our learners. We need to practice a new language to use it confidently and check we understand.

The understanding of science concepts can be further deepened using means beyond reading and writing. By using pictures, presentations, drama, debate we can reinforce learning and critical thinking, while also enhancing enjoyment and participation.

On top of this, the technology available to us is constantly evolving. It provides new ways for us to communicate science by literally putting the world at our fingertips.

These strategies do not need to replace learning with books or writing about science, but they can complement it. Teachers, parents and carers who demonstrate a wide variety of ways to communicate about science will enable children to become more effective communicators themselves.

Back to blog

QUICK

QUICK

MEDIUM

MEDIUM LONG

LONG